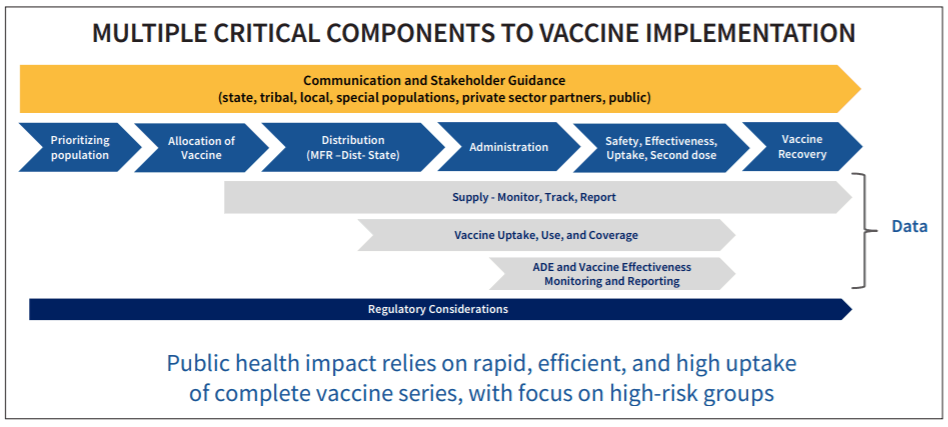

As we all eagerly wait for the approval of safe and effective vaccines for COVID-19, public health agencies across the U.S., led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Defense (DoD), and state departments of public health, are working hard behind the scenes to create a plan that will help ensure efficient and effective distribution of a vaccine as soon as one is ready. Yet, the many unknowns – which vaccine candidates will prove effective, which work best for which populations, what are the storage and handling requirements, what quantities of the vaccine will be available at approval, and manufacturing capacity post-approvals – are forcing these agencies to rely on past experience and existing systems to create a plan that they hope will work for many as quickly as possible.

On September 16, CDC and DoD released an interim playbook alongside a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and DoD strategy memo that both seeks to explain how the federal government, through Operation Warp Speed, is preparing to distribute vaccines to the states, especially right after FDA approval when supplies will be limited.

The biggest outstanding question is who will receive early access to the vaccine post-FDA approval when supplies are expected to be limited. According to the CDC’s current plan, healthcare personnel (e.g. employees at hospitals, healthcare facilities, long-term care facilities, pharmacies, EMS, etc.) will receive first priority in Phase 1a, followed by essential workers, those with high-risk medical conditions, and adults over 65 in Phase 1b. CDC estimates that these populations combined is up to 250 million Americans – more than 2/3 of the total population. So, looking past the estimated 17-20 million healthcare workers eligible for the vaccine in Phase 1a, there are still many decisions to be made on the federal and local level about prioritizing populations within Phase 1b and who gets to make those rulings.

Alongside these decisions is the question of how to most effectively address the extreme health inequities from COVID-19 where minority populations across the country are getting sick and dying at disproportionate rates to whites. Thankfully, CDC and state health departments are thinking about this carefully as it relates to vaccine distribution. And because minorities can make up large percentages of sectors within healthcare workers, essential workers, and those with high-risk medical conditions, many within minority populations are already incorporated into Phase 1 vaccine access.

The good news is that despite the many unknowns, states have lengthy experience in effectively distributing routine and seasonal flu vaccines and can draw on lessons learned from their 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccine response plans. In fact, Massachusetts has one of the highest rates of vaccinations in the country. Looking forward to when a vaccine is ready, we can expect, that despite the many uncertainties, this experience, lessons learned, and existing vaccine systems at the state level will greatly benefit early distribution and help us prevent further COVID-19 infections to ultimately reach population immunity faster.